The Incredible Talking Machine – Manchester and Machinery

Here are some of the images which inspired the book – click on each one for the story behind it, and scroll down for the historical notes from the book.

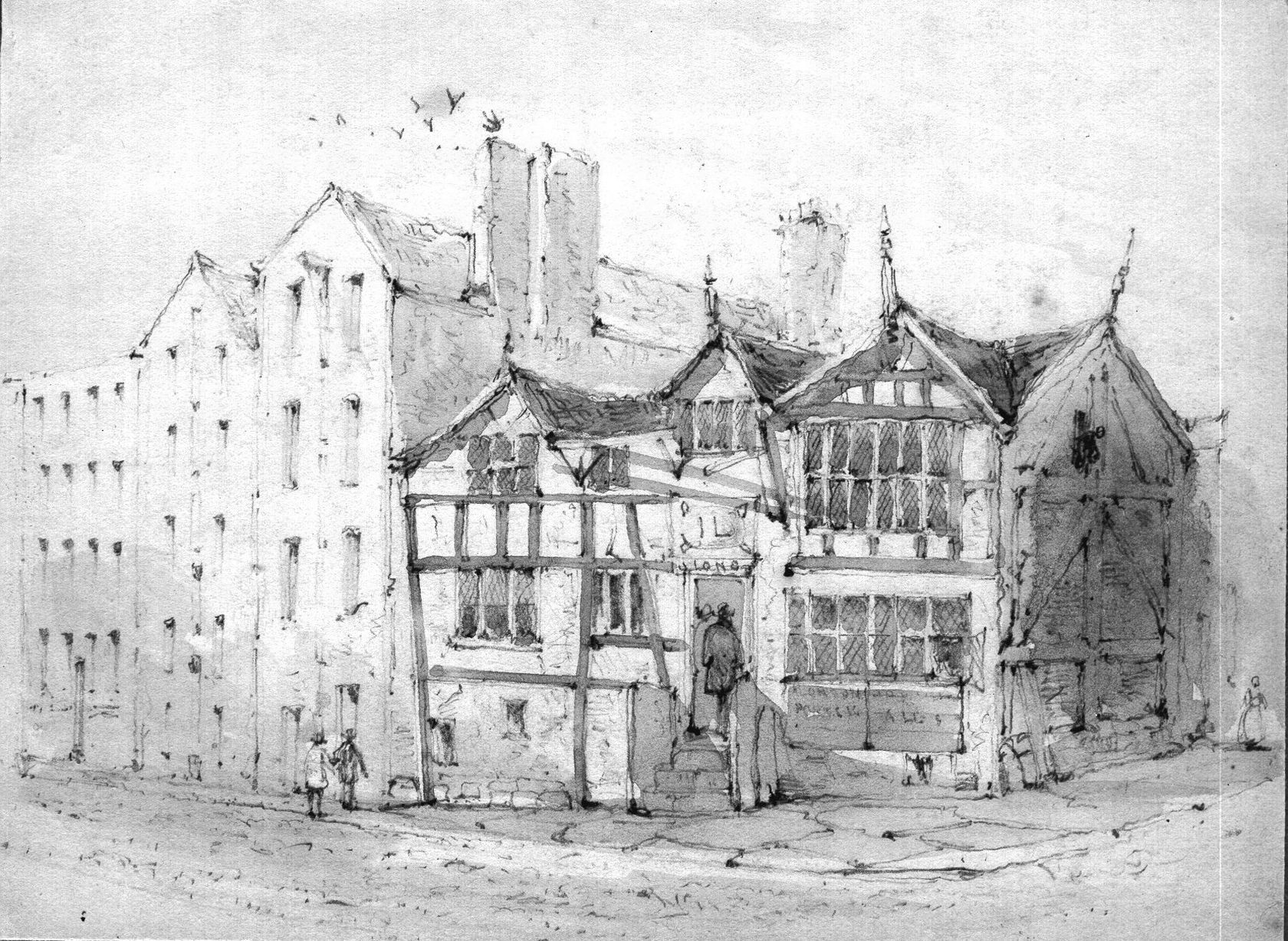

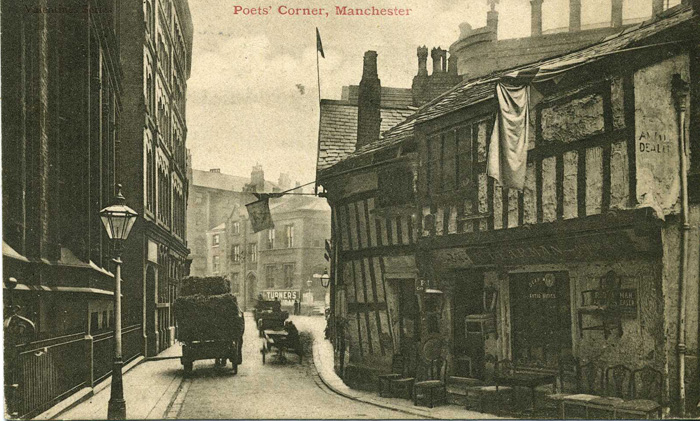

In 1848, Tig’s Manchester was crowded, noisy, and expanding fast.

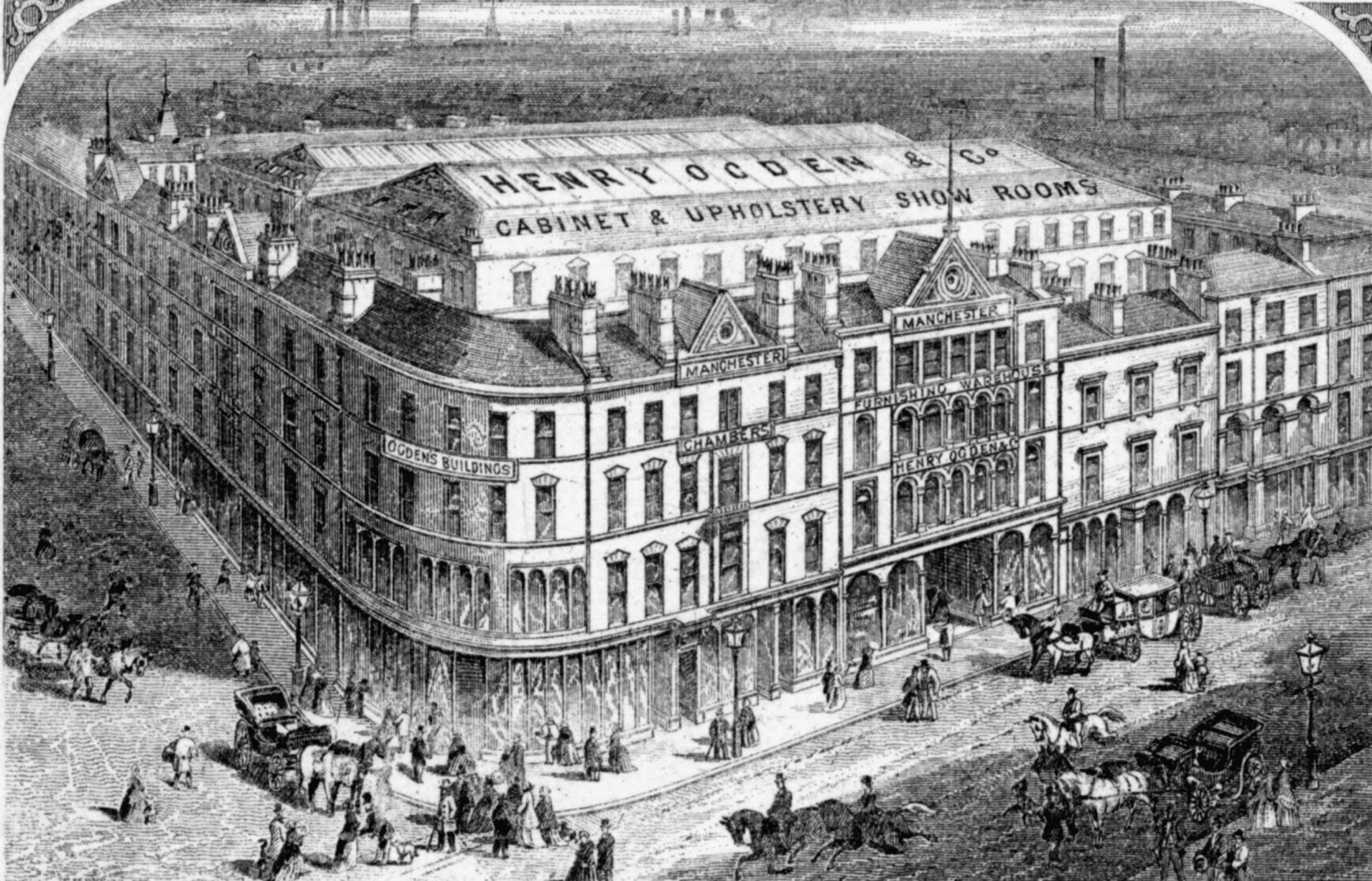

Vast mills worked day and night. Deafening and dangerous machinery spun raw cotton into threads and wove threads into fabric to be sold all over the world. Less than a hundred years earlier, these jobs had been done by hand. Now huge steam powered contraptions had taken over and people flocked to the cities in their thousands to find work in the mills.

The people of Manchester were compared to worker bees, swarming in and out of the mills, always busy, always working, tiny parts of a vast hive of industry. Look closely in Manchester today and you’ll find bees hidden everywhere – a symbol of Manchester’s proud and difficult history.

As the mill owners got rich, the people who actually did the work had hard, short lives. Days were long, wages were low, and safety was non-existent. Poor people lived in awful conditions – whole families living in a single room and whole streets sharing a single outdoor toilet.

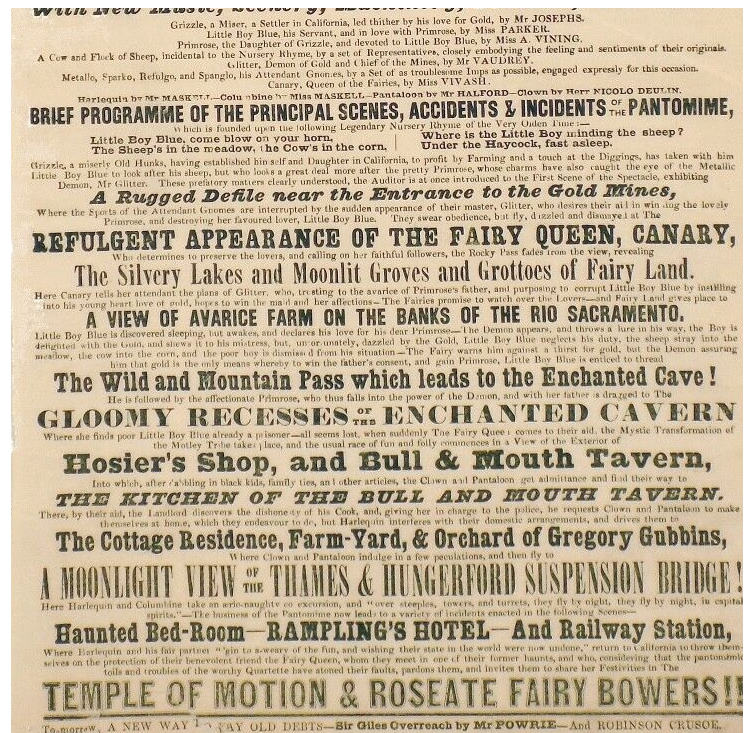

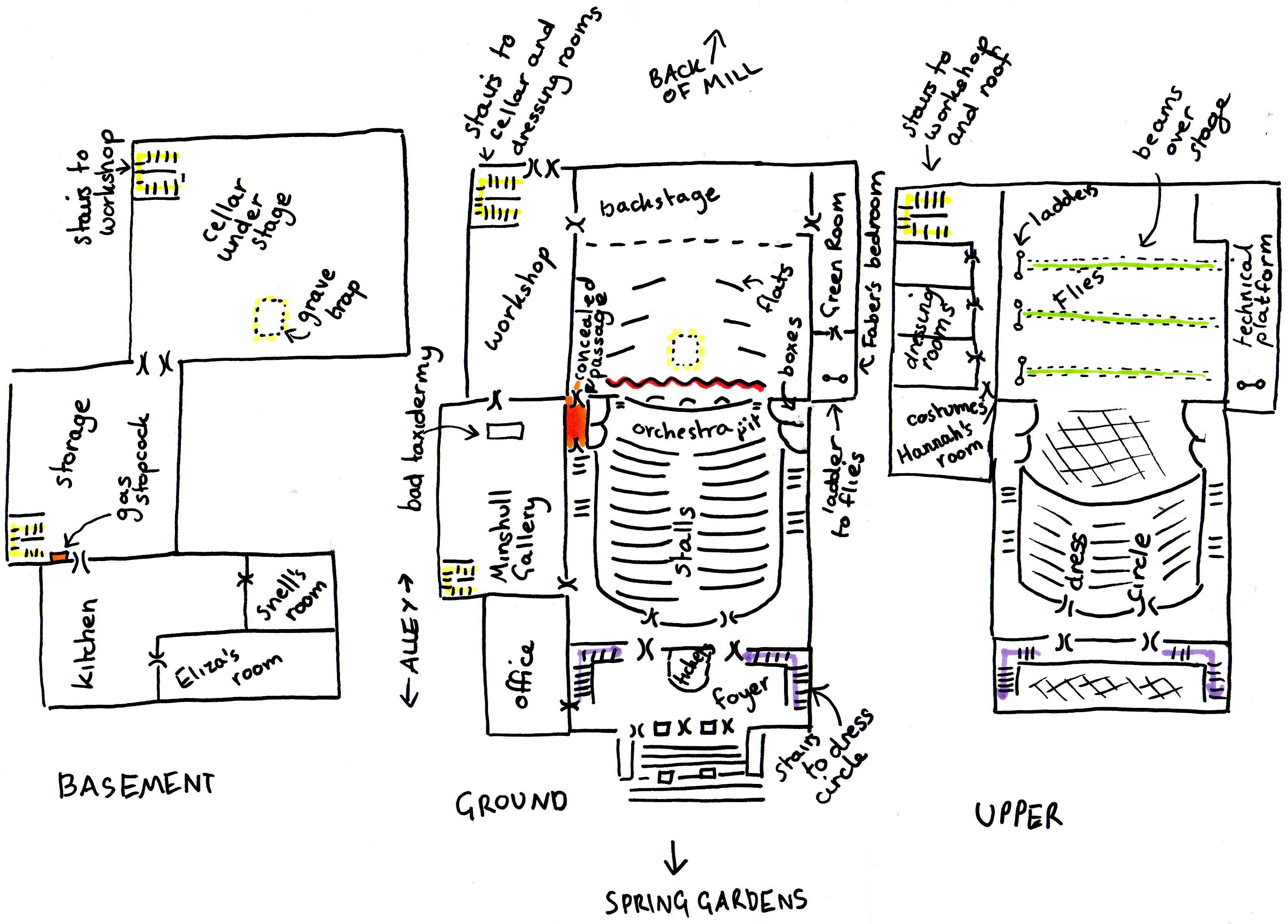

Factories were not the only places taking advantage of new inventions. Theatre machinery made actors fly above the stage and disappear through the floor. Gas lights allowed them to make shows more spectacular than ever. The 1840s was the beginning of magic shows and stage illusions. Inventors made amazing automata – complicated clockwork toys which could do difficult actions like walking, dancing or even writing.

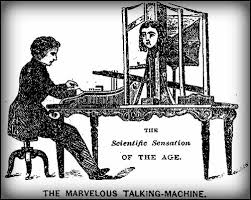

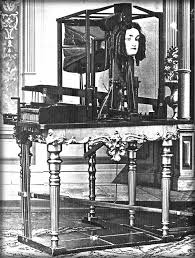

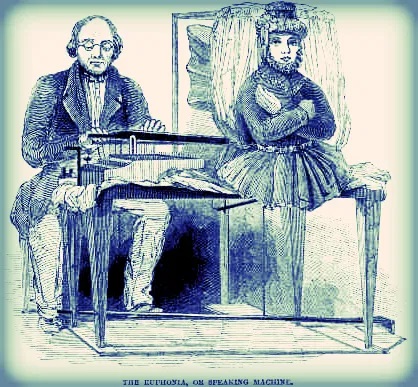

It was this world of magic and machinery which produced the real Joseph Faber and his talking machine.

It’s hard to overstate how incredible this invention was. This was years before the first sound recordings were made. If you wanted to hear a song, you had to go to a show, or sing it yourself. Telephones were still decades away – no one had ever heard a voice from a machine. Euphonia was incredibly sophisticated, and Faber had spent years perfecting her.

Unfortunately for Faber, everybody hated her.

Euphonia’s voice was flat and unnerving – one witness wrote that it sounded like a voice from the depths of a tomb. Her face was realistic, but only her lips and tongue moved, which audiences found creepy. Faber was a genius but not much of a performer. He was said to look untidy, even haunted, and to be completely obsessed with his invention.

Though Faber never got the credit he deserved, some people did recognize how special Euphonia was. One was American scientist Joseph Henry, who played a big part in inventing the telegraph (the first machine which could send messages over long distances electronically). He thought the two inventions could be combined, so a message sent by telegraph would be spoken by the talking machine at the other end.

Another notable fan was Melville Bell, who studied how speech is produced and found Faber’s work inspiring. You may have heard of his son, Alexander Graham Bell, who invented the telephone. Lucky for us he did, or we might have mechanical talking heads in our living rooms instead.